A book by Herb Stevenson, Volume 1. Learn more on Amazon.

Thoughts II:

The Next Step: A Calling

Volume 2 of 3. Learn more on Amazon.

Thoughts III:

Creating The Container

Volume 3 of 3. Learn more on Amazon.

To Lead

Read the article about training with Herb Stevenson in ALN Magazine.

See the article...

The Impact of Organizational Culture on Coaching: Part II

by Herb Stevenson

In the April Issue, we reviewed Schein's three primary cultures within every organization: (1) Executive/C-Suite, (2) The Engineering, and (3) The Operators. Cultures as defined therein are the unwritten (and often undiscussed) rules of success for the respective functional areas. Because the cultures are created over time, "the ways things get done" are assumed to be the "right" and possibly "only" way. Because these cultures generally do not take the time to learn how to engage and therefore to be open to dialogue, the chances for misses in the organization and therefore in the coaching process is quite high.

Right to Bitch

One of the cues that there is a culture gap between the functional areas is the coaching client has a tendency to blame or bitch about another person or group. Typically, this means that the coachee is self sealed within the meaning making process of the functional area. The ability to examine core assumptions that are being made is minimal.

I coined the phrase "the right to bitch" over the years as means to create a sense of empathy with the client. Typically, I attempt to normalize it as a human process when people become frustrated and feel lost as to how to overcome the problem. Often, I add humor and examples so they can see that it is common. Once, I've established the fact that "bitching" exists, I move to create self awareness that (1) due to their frustration, they are in fact bitching, (2) it serves no function except to further disempower them by acting as if someone else must change to get to a solution, and (3) there are ways to overcome the need to bitch by finding inroads to the other culture.

The Basic Assumption

As noted in the April article, each of the three cultures have a unifying set of assumptions that are treated as gospel if not incontestable facts about not only getting work done but what is wrong with the other culture. Moreover, these cultures do not interact beyond transferring information between each other concerning what work is to be done, when, and typically under strict conditions. Generally, they function as separate entities bound within the overall organization. We often call them silos similar to the figure below.

Communications does flow between the various group via managers, however the culture filters the communication with emotionally laden meaning; ergo the resulting blaming and bitching.

Overcoming the Separation

When coaching between these organizational cultures, the first goal is to discover the core assumptions that has led to the frustration and resulting bitching. The three cultures described in the April article is a simple way to listen for the core assumptions from which the client identifies: C-Suite, Engineer, Operator. The assumptions will be embedded in what the client sees as the correct way to think about the problem and the incorrect way of the other culture. Once these are identified, I ask what is it about the other group or person that frustrates the client. There tends to be a lot of statements about what the other person does to block them or does not do to support them. As we progress, I ask if they have had any conversations with them directly about the issues. The answer is a mix between "no", "you don't understand", and "it is not that easy".

Building Common Ground

Culture conflicts typically have emotional charges that are difficult to diffuse. The first thing I attempt to do is create more understanding about the other culture. Providing information in articles or books can build a common language very quickly from which to expand the awareness of the client. If the clash is between the C-Suite and one of the other cultures, I lean toward articles that describe the difference between managers and leaders or the issues faced by line managers versus executives. The goal is to begin to realize that everyone is on the same team and the focus must move from disdaining differences to embracing differences to maximize success.

For example, one of my clients was a team of regional sales managers that were strategically located around the country. Due to the nature of their work, they traveled extensively and rarely made the trip to the home office except for rare occasions. They referred to the home office as some distant place and the executive leadership as foreign beings that had trouble listening to their need for support. Moreover, they referred to themselves as outlanders.

The decision was made to meet with one of the more vocal regional sales managers to begin the coaching process. After he gruffly explained all the woes he was facing and how the main office not cooperating, we started a series of readings on managing versus leading. He noted he liked to read, so I tossed him the Leadership Pipeline to read on the plane. As many of you know, the Leadership Pipeline describes how each level up the organization requires a different way of thinking than the prior. Moreover, the likelihood of failure increases if the individual does not learn a new way to think in order to succeed. The next month, the client returned with the book. We had a lively discussion on the differences in how to be successful in the C-Suite and in his group of regional sales managers. Suddenly, he had an interest in understanding not only the C-Suite but other foreign areas, such as accounting, finance/ credit, and sales support. As we progressed over the next several months, we discussed how to build inroads to each of these areas from a perspective of understanding the differing needs and how each might support the other to be successful. Rather than fly in occasionally to complete some task and immediately fly to the next location, similar to how he functioned as a regional sales manager, we experimented with straying longer to meet with the critical areas that were frustrating him. In time, his appreciation for each of the troublesome areas increased. More importantly, the organization was no longer a thing, but a group of people that were supporting his success. He no longer felt like an outlander.

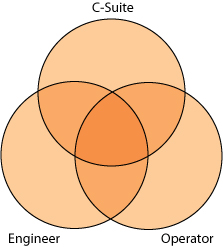

Over time, we returned to the book to address the focus of executives in the C-suite. As we explored the differences, he developed an appreciation for the stress faced at the top. In addition, we began a process for him to begin to learn how to influence up. This included providing more field information that could be useful in strategy sessions. This led to a new intelligence gathering process to support the organization. In addition, he became comfortable enough to request a meeting with the CEO. Instead of complaining and blaming, the meeting took a positive turn for what was working and what could be done better. Both came out with an appreciation of the others daily duties and responsibilities. Several years later, the rest of the regional sales managers have gone through a similar process. As each one goes through the process, they have built an overlapping understanding of the other cultures in the organization. This overlapping understanding supports each culture to use the time tested ways to success while ensuring that silos do not develop. Rather, the appreciation of the other cultures creates the understanding necessary for each culture to work well with each other.

Overlapping Cultures

As coaches, our goal should be to support greater understanding and appreciation for competing cultures within the organization. The C-Suite will always be focused on the larger organization with a concentrated eye on performance. The engineers, accountants, etc. will always be focused on the design of repetitive accuracy and success for their respective systems. The operators will always be focused on getting the day-to- day work done. Rather than oppose each other, the organizations that are able to overlap the cultures without diminishing what makes each culture successful will always be more successful. The overlapping areas between each culture is how the work is translated into working language. The "sweet spot" where all three cultures overlap is where alignment between all areas is created, thereby insuring greater success.

As coaches, our goal should be to support greater understanding and appreciation for competing cultures within the organization. The C-Suite will always be focused on the larger organization with a concentrated eye on performance. The engineers, accountants, etc. will always be focused on the design of repetitive accuracy and success for their respective systems. The operators will always be focused on getting the day-to- day work done. Rather than oppose each other, the organizations that are able to overlap the cultures without diminishing what makes each culture successful will always be more successful. The overlapping areas between each culture is how the work is translated into working language. The "sweet spot" where all three cultures overlap is where alignment between all areas is created, thereby insuring greater success.

Role of the Coach

As executive coaches, our focus is how to determine if the organization's internal cultures have fossilized into silos. If there is minimal permeability between the cultures, then there is a cultural dynamic that should be included in the coaching. Otherwise, the process will address only behavioral changes which often are not sustainable.

My goal throughout these processes is to create awareness of the various cultures, to humanize the different cultures as people doing the best they can, and then to build a method of engagement between the cultures. Engagement in this context is to remain in dialogue regardless of differences in the desire to find a workable solution. The lack of engagement is often what causes the breach between cultures. Once the cultures are fossilized, each culture tends to drop anchor around what is true and what is false. Once the anchor of cultural truth is dropped, the tendency is to move toward irrational and highly emotive reactions. Blame and shame surfaces leading to bitching. As such the emotional charges prevent staying engaged because the cultures have moved into a divide and conquer mentality without realizing that we are our own enemy.

Much of my role throughout is to create safe experiments for new behavior that can lead to self discoveries. These discoveries are about being on the same team, that both sides are frustrated, and that solutions can only be developed when blaming stops and true dialogue for solutions begin.

Our role as executive coaches is to remember that besides the common cultural differences that derive from different religions, nationalities, and ethnicities, there are evolving and self sustaining internal cultures within our organization. These cultures are embedded in who we are as an organization.

References

The Leadership Pipeline: How to Build the Leadership Powered Company. Ram Charan, Stephen Drotter, & James Noel, 2011.

The Dynamics of Taking Charge, John J. Gabarro, 1987.

Organizational Culture and Leadership, 4th Ed. Edgar Schein, 2010. In particular, Chapter Four: Macrocultures, Subcultures, and Microcultures, pp. 55-71 The Impact of Organizational Culture on Coaching: Part II Page 6 of 6

We Appreciate Your Feedback

Please let us know if you found this article interesting or useful. We will not submit this information to any third parties.