A book by Herb Stevenson, Volume 1. Learn more on Amazon.

Thoughts II:

The Next Step: A Calling

Volume 2 of 3. Learn more on Amazon.

Thoughts III:

Creating The Container

Volume 3 of 3. Learn more on Amazon.

To Lead

Read the article about training with Herb Stevenson in ALN Magazine.

See the article...

Hi folks,

A busy time as Spring is starting to show up. Recently, I completed a single day workshop at the Gestalt Institute of Cleveland on Coaching at the Point of Contact. The model continues to evolve and has been captured in the soon-to-be-published article at the Gestalt Review. I think coaches will find it insightful and supportive to their practice. Thoughts and comments are welcome.

I am providing the week-long coaching workshop at Punderson State Park again in April. Details are below. Each year, we have groups of 8-10 that enjoy the skill-building while gaining personal and professional insights. I look forward to seeing you.

Respectfully,

Herb Stevenson

Herb Stevenson, CEO/President

Cleveland Consulting Group

Coaching at the

Point of Contact:

A Gestalt Approach

Herb Stevenson

About 30 years ago, I was part of a consulting firm that provided training to banks. While in Georgia to conduct a client training over the course of three days, I had an indelible moment. This is a moment when something occurs that will either change a relationship you are in, or change how you engage with the world in general. Usually, you realize it was that kind of moment in retrospect, although the realization can be immediate, as well. In my case, it was both; I understood what had happened within seconds of it happening, as well.

The night before this bank client training concluded, I went to dinner with the workshop sponsor, who I’ll refer to as “X,” and two members of X’s support staff. As the night progressed, it became obvious that these staff members had consumed too much alcohol, especially as they’d begun “beating up on the boss” by making snide remarks. During this period, X, did not react (and I wasn’t sure whether this was a deliberate decision or whether he’d just gone into a type of denial). In any case, I decided to step in and use the Gestalt intervention of reversing the polarity.

“Is there anything that X does well?” I asked. Both staff members were momentarily stunned. Perhaps because they suddenly realized what they’d been doing. Or because I’d interrupted their “story” (as a Gestalt coach tends to do). While their silence grew increasingly uncomfortable, I cited several of the best practices that I’d observed X, the training’s sponsor and their boss, implementing over the several years we’d spent working together. The two staff members agreed that X had, indeed, done these things. Then they ended the conversation by saying they’d had too much to drink and should go to bed.

The next day, as I was getting my bags from X’s car to run into the airport, he thanked me for what I’d said to his staff members the previous night. Unfortunately, I responded noncommittally because I was focused on making my flight. “No problem,” I said, and hurriedly walked away, headed toward the airport entrance. In my peripheral vision, though, I saw that my client had reacted poorly to my less than heartfelt response. In fact, as I almost immediately realized, this was an indelible moment – and it was a moment from which our business relationship would never recover. Within 24 months, our relationship was struggling and imperiled. What had always been easygoing and relaxed became highly strained, and then completely severed. I’ve spent the 30 years since trying to understand not only what happened, but what I can learn from what happened.

Indelible Moments

Using this disastrous experience as a touchstone for exploration, I began to study how people often miss the mark and fail to respond meaningfully to each other, during what I’ve come to call an experience of “spontaneous piercing,” or an unexpected and instantaneous vulnerability. This can occur when a client suddenly feels exposed or embarrassed -- either because s/he said more than s/he feels is appropriate, or because s/he became unexpectedly emotional -- and the coach is not adequately present to support the client, and so, does not mitigate or erase the uncomfortable feeling of being exposed. If, on the other hand, both people remain fully present, this can become an intimate moment that either results in a change between them, or within one or both of them. Such a moment becomes indelible if it is remembered as that particular point in time when a significant interaction changed one or both individuals and, as a result, their relationship (and perhaps the way they relate to others, as well).

As coaches, we might see versions of these moments occurring with our clients. It might appear that your client is suddenly connecting with you as a coach, or connecting to the coach work, such that s/he can make the necessary changes to more fully be the leader s/he desires to be. This can often feel like a vulnerable moment that is leading to some type of intimacy for the client, and possibly for the coach. However, what we may miss in these moments of vulnerability is that things can easily go awry, as they did with my client X, thus blocking further progress, instead of leading to a breakthrough moment. When this negative outcome occurs, the client may be at a sudden loss for words, or become embarrassed, or shut down and re-armor, and may also become enraged.

As was the case with my friend, I misread the moment and failed to recognize that he was trying to connect with me at a heartfelt level. My eagerness to run into the airport and get away probably left him feeling exposed and, as a result, quietly enraged. Rather than an intimate moment of appreciation and connection, this incident ended as an indelible moment that also ended our business relationship.

Presence/Vulnerability Dynamic

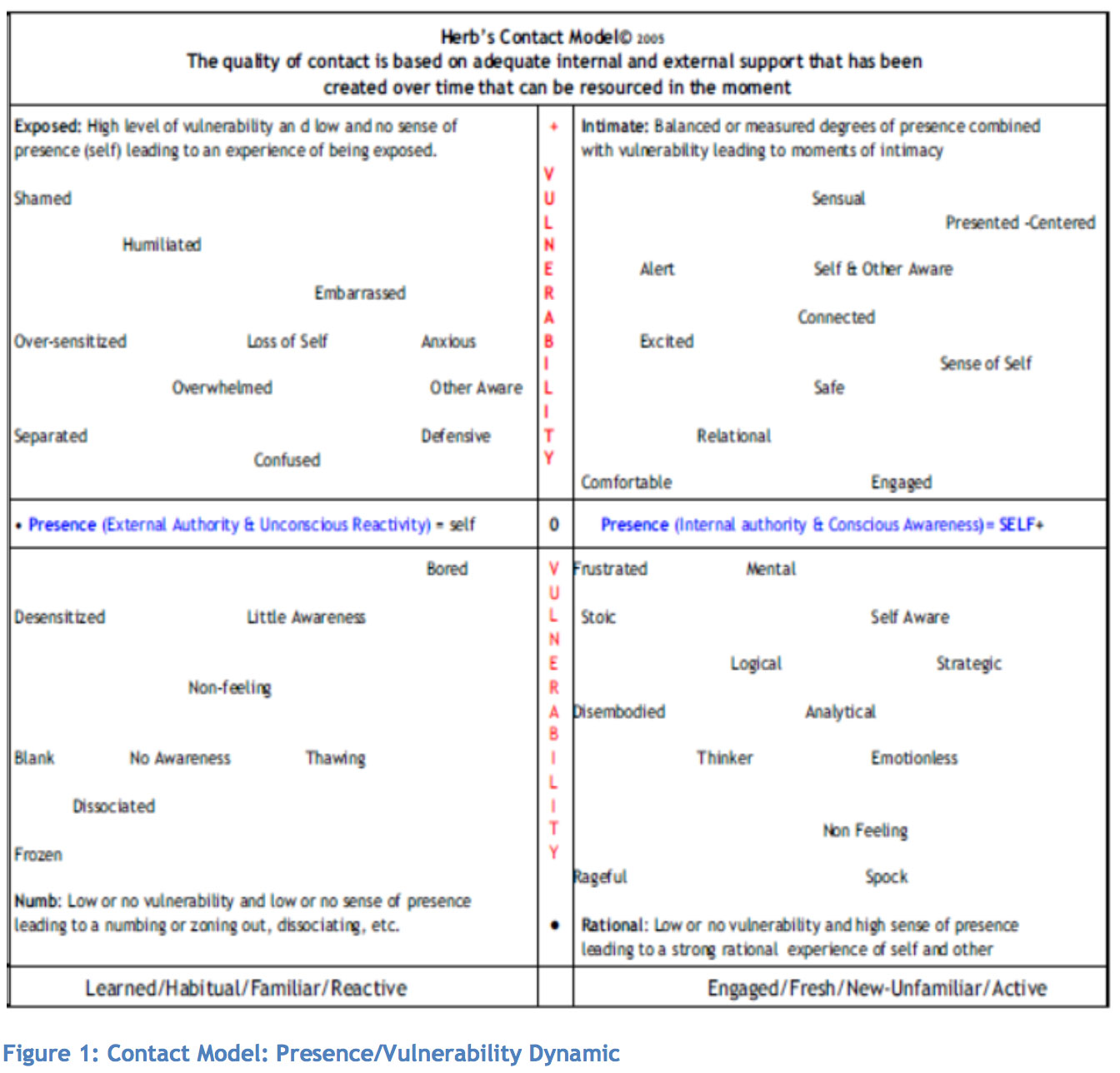

Over the years, I have studied these indelible moments with clients, and discovered a dynamic -- an ongoing dance -- between vulnerability and presence that, when balanced, can lead to a moment of insight or intimacy. But when this ongoing dance is out of balance, it can result in the client and/or coach feeling embarrassment, humiliation, or shame (see Figure 1, depicting a two-by-two table of the Presence/Vulnerability Contact Model).

A Love Story

If you will allow me a little leeway, one way to better appreciate the presence/vulnerability dynamic is by remembering a youthful experience of unrequited love. Recall when you first fell in love, and how it was a heart- pounding, feeling-good-all-over sensation. Clearly, all was “right with the world,” as true love was yours. But when you expressed your feelings to the one you loved, suddenly everything changed. Your feelings are not reciprocated and, instantly, you feel heat rising into your face, as it burns with embarrassment. You wish that you could take back your earlier declaration of love, and also find a place to crawl into and hide. Your breathing becomes labored as you search your memory for cues that your love was not returned, and would never be. You now feel totally dissociated from your body and your mind, and this is a welcome source of protection, as you remove yourself from the presence of your former love. Over the next few days, you cycle repeatedly between wondering how you could have been so stupid, and amazement at the speed with which you went from feeling ecstatic to miserable. In time, you tell yourself and others stories about “what really happened.” Some stories are told to save face with friends, some to express your hurt and anger, some to understand what happened, and some simply to console yourself in the despair and darkness that is the emotional hell of being rejected in love.

What Happened

The contact model can walk us through such experiences by using the presence and vulnerability dynamic. See Figure 1 to track the process. Falling in love is the experience of complete presence and vulnerability that allows intimacy to be experienced as comfortable, relational, engaging, safe, exciting, connected, possessed of an alertness that is like a refined clarity of self and other, sensual, and consciously present-centered. As long as a balance is maintained between being fully present and vulnerable, and being able to manage this dynamic, the experience of being in love can survive. But when we are surprised by an indelible moment – when we learn that the one we love does not love us back -- we may lose our sense of self and move into the exposed quadrant. In this place, high vulnerability and little or no sense of presence (of self) results in a range of emotional reactions, in feeling defensive, confused, separated (from self and other), overwhelmed, over-sensitized, anxious, panicked, embarrassed, humiliated, and shamed. In fact, this experience can lead to an overall feeling of wanting to vanish (a further loss of the sense of self).

To draw a parallel between the experience of unrequited love and any situation in which we have a preconceived idea that is not validated by a situation, by facts, or by other people, the feeling of surprise and shock can be very similar in both cases. Depending on our internal recovery process (our resilience), we can become defensive or anxious, or in a worst-case scenario, embarrassed and humiliated by being “wrong.”

The presence/vulnerability dynamic is capable of shutting us down emotionally, when we are stuck in the exposed quadrant. Energy related to the shock of being exposed begins to redirect and reduce (or shutdown) our vulnerability. When this occurs, we tend to move into the quadrant where various forms of numbness can develop. Specially, we may slowly move into boredom, diminished awareness, overall desensitization, a state of non-feeling, a blank mind (zoned out), dissociation, or even become internally frozen if prior trauma is triggered by this experience. We will now experience the self-protection of very low or even zero emotional vulnerability, in combination with low or zero presence. (This easily compares with the experience of unrequited love since overwhelm causes the instinctive shutting down of our overloaded “internal circuits.” It’s important to note that this reaction may occur in the space of a few milliseconds.)

As we saw above, over time, we explain what happened to ourselves, or rationalize it, and as we do, there is a return of our sense of self which establishes a strong rational experience of self and other. While this process of restoration is occurring, the sense of self may involve a confusing range of emotions that are presented to the coach. These emotions may include everything from frustration to highly cognitive, or intellectualized, responses, in addition to logical, strategic, stoic, disembodied, analytical, and low affect responses, and occasionally, expressions of rage. In many ways, this is a period of recovery, in which feeling overwhelmed by vulnerability leads to a complete shut-down, so we can make sense of what has happened to us. Interestingly, this dynamic tends to occur in any situation in which we instinctively move away from being fully present and anchored in our sense of self1.

Theoretical Underpinnings

Present-Centered/Presence

From its inception, Gestalt has been "present-centered" (Perls, 1992; Perls, Hefferline, and Goodman, 1994). This focus on present-centeredness is based on the understanding that everything in life occurs in the here and now. Even a memory must be re-lived in the present moment, and is therefore better served if brought fully into the vibrancy and immediacy of the present -- rather than being fixed in the mind like an old, often-repeated tale (Latner, 1992; Perls, Hefferline, and Goodman, 1994). The true significance of present-centeredness is well illustrated within the realm of character. Gestalt defines character as "what we do characteristically." That is, "the typical ways in which we function emotionally, physically, intellectually, spiritually" (Latner, 1986). But the usual, the habitual, and the unconscious can be retrieved and brought into our present awareness, where they can be reconstructed, re-experienced, and re-examined, both freely and at length. It is during such moments of reflection that the presence/vulnerability dynamic can lead to a point of contact that either leads into or away from an insightful awareness2.

For example, in writing one of my earlier articles, I personally experienced the presence/vulnerability dynamic, and how it can bring one’s painful history into the present moment. I knew that I have an unconscious memory of my high school years, in which I struggled with teachers who told me that I asked too many questions. They labeled me “stupid” because of my many questions (also because football players like me were thought to be big, strong, and dumb). One teacher, in particular, still affects my relationship to writing -- as I discovered when working with the action editor on that article. My initial response was excitement when I got a green light to move straight into the blind review process, and reviewer feedback included suggestions to improve some areas with the idea of moving forward to publication. So when the editor and I met to discuss the reviewers’ changes, I felt confident they could be made quickly and easily. However, the editor instead told me the article would be more valuable if it were written from an applied rather than a theoretical perspective. And, it was added, if I wanted to keep my theoretical-illustrated-by-examples approach, she would need to transfer me to a different editor. The problem was, after hearing this last comment, I shut down. To compensate for having my unconscious writing-teacher memory triggered, I asked the editor to put her comments in an email. My past history pushed me into numb dissociation that lasted for several weeks, and it only took microseconds for me to move from excitement (and vulnerability), to feeling overexposed, to shutting down completely---a move from Quadrant 1 to Quadrants 2 & 3.

Most of us have unconsciously held memories that, when triggered, force us into a period of self-protective shut-down. In this instance, I was as blind as the editor in what had happened. Neither could speak of it as I had dissociated and the editor was waiting for revisions. As time progressed, I was able to begin to thaw the dissociation and return to an analytical presence that was able to unravel and begin to correct the situation.

Witnessing

When gestaltists and gestalt coaches try to contain and describe what their client is saying and doing here and now, their focused examination is usually described as paying attention to what is. One source of this concept of present-centered awareness is the Buddhist tradition, in which what we call present-centeredness is known as bare attention. This type of attention is concerned solely and exclusively with what is in the present. Living with full awareness in the "here and now" permits us to be quiet (within ourselves and with the client), as observing witnesses of our experiences, ourselves, and our clients (Thera, 1962). Moving out of the here and now invites projection of the past and anticipation of the future to move in, and crowd out the present. But the past -- or the future -- because neither are present-centered, become an "illusion [that] ensnares us in its recurrence" (Naranjo, 1993). The illusion is created by a nanosecond-long leap across the present into a (preconceived) perception from the past, or an imagined future, thereby short-circuiting the reality of "what is" actually happening in the present moment.

A subtler, yet perhaps more powerful, way of using “bare attention” is by serving as the client's witness. As we focus on the "here and now," we witness the client in the present. Our mind grows quiet but fully aware of both the internal silence and the client. "The presence of a witness," Naranjo argues, "usually entails an enhancement . . . of attention and of the meaningfulness of that which is observed . . . The more aware an observer is, the more [the client’s] own attention is sharpened by [the observer's] mere presence, as if consciousness were contagious . . ." (Naranjo, 1993). It is at these moments, in which the gestaltist’s presence can contain3 the client’s vulnerability, and support him/her in seeing beyond the past or pulling the future back to the present moment. Such contact with the present seems to dissolve those perceptions blocking new behavior or the awareness needed to move forward. Insight then surfaces and permanent change occurs.

If we return to my triggering experience while having a prior article edited, this healing witnessing dynamic played out in the following way: Acting as my own witness and using the contact model, it became clear I had brought my negative teacher experience into that moment. Past embarrassment and shame had surfaced in a flash, shoving me into the safety of dissociation. As clarity about the process came into focus, the editor and I began a dialogue about what had happened. Initially, she was surprised to hear of my reaction. We discussed multiple realities including my projection onto her and the editing process. As a result, my ability to once again consider how to rewrite and revise the article returned. Using the contact model, we were both able to understand what had happened and what could be learned. The editor realized that her suggestion had triggered my silence, followed by my request for a written version of what she suggested, because I had by then dissociated so severely I could no longer understand what she was saying. Because we followed the model through to completion – rather than aborting the activity at some point -- we were both able to learn and move forward.

Significance

There is an interesting dynamic concerning the need for validation from our self and from others. This is underscored by the way our total interdependence suggests the immense relational depth between presence and vulnerability, within the context of making contact with self, other, and the environment.

Our interdependence becomes clear within the context of how we understand human significance. “Significance refers to one’s sense of having value in the eyes of others” (Klein, 1991), and this is, of course, vital to the emotional well-being of every human being. In day-to-day life, significance is created or discovered through interacting with family, friends, and colleagues; gaining recognition and rewards for one’s achievements; participating in social or interest groups; working with others for a common cause; and celebrating one’s national, racial, ethnic, or other identity. “Moreover, significance . . . is fostered by exposing people to environments in which they can realize their potential because they know they are needed, wanted, and valued by others who are important to them” (Klein, 1991). In Gestalt (and many other theoretical fields) we refer to significance as being validated by our sense of self, or by our experience. Often, it is described by clients in sensory terms, in such statements as: “I feel seen,” “I feel heard,” or “I feel validated.”

Returning once more to the process of editing the prior noted article, I had struggled to discover my internal sense of significance (during adolescence) surrounding writing. As such, my efforts to self-protect held a fear of embarrassment hovering in the background. Working with the editor, though, I was able to move through dissociation and return to making contact in a balance of presence and vulnerability in order to complete the article.

Contact

If presence functions to create a container for change, then what is it that occurs within this container? In Gestalt terms, we refer to what occurs in presence as “contact.” Contact is the psychological process through which I allow myself to meet myself (as in memories and imagination); or to meet a person, group, or organization; or to meet the environment. I can accomplish this most effectively by staying present-centered.

Contact, then, does not mean togetherness or joining, but actually refers to a heightened awareness of the distinction between ourselves and what is "outside" the boundary of our selves. This boundary, moreover, is porous, but holds the two concepts of self and other apart, while permitting interaction and exchange. As explained by Polster and Polster, "The contact boundary is the point at which one experiences the 'me' in relation to that which is 'not me' and through this contact, both are more clearly experienced" (1973).

Within the vulnerability/presence dynamic, we begin to realize that contact requires a degree of vulnerability (openness to self and others), and sufficient presence to contain, receive, and support this vulnerability. Without adequate presence (a form of internal authority/ significance that allows us to both meet and be oneself), vulnerability will increase anxiety and throw the moment into a past experience -- a meaning-making diversion that can lead to embarrassment, a sense of humiliation, and potentially, shame. Often, any of these three feelings will lead to a numbing or dissociating process that causes us to feel as if we have left our body (as happened for me while revising the prior noted article).

This sense of contact is supported in gestalt theory. Prominent theoreticians have observed that our self-concept is constructed from our experiences, which are in part determined by the range of our "capacities for assimilating new or intensified experience" (Polster and Polster, 1973). The individual maintains a sense of self through "I-boundaries," that is, through establishing "bounded limits" that determine how s/he "either blocks out or permits awareness and action at the contact-boundary" by determining what is not me. This serves to "govern the style of life, including choice of friends, work, geography, fantasy, lovemaking, and all the other experiences which are psychologically relevant to . . . existence" (Polster and Polster, 1973).

We often find that, "Within the same individual there will be both the mobilization to grow in some areas and the resistance to growth in others," so that the I-boundary is inconsistent in blocking or opening to the other (Polster and Polster, 1973). Conscious and unconscious emotions, symbols, and thoughts that are typically split off from the self and/or projected onto others can emerge from within the client. Frequently, these serve the function not only of establishing meaning, but of containing (framing and holding in place) anxieties. If placed into a vulnerability/presence dynamic, the I-boundary becomes the point of power (or fails to) for the client. S/he might decide that, “If I am more fully present with myself, I will likely be able to face a certain degree of vulnerability, even to aspects of myself that I have been unable to face until now. If I am less present, or some of my blocked aspects of self leak into my awareness too quickly, my vulnerability will likely accelerate to the point of total overwhelm, leading to numbing or dissociation.”

To support the client in meeting with or extending appropriate contact boundaries, the Gestaltist makes contact tolerable for the client by containing (framing and holding in the form of bare witnessing and, when necessary, taking boundary-maintaining action), and by gradually re-presenting to the client her/his emotions, symbols, and thoughts in the form of words or silence (Billow, 2000). As a result, the function of containing is primarily transformative. It is accomplished by the coach being fully present, which s/he does by showing up without preconceived notions, while being able to take action or set boundaries, as seems appropriate in support of the client. The coach stays at the I-boundary of self and the client by being able to connect and feel into the situation, while being able to pay attention to what has heart and meaning (the edge of vulnerability) for the client and for him/herself.

In the illuminating situation resulting from editing this article, neither the editor nor myself had any idea that a parallel process between the article content and the contact model was evolving. But by staying engaged, in order to let a sense of what had happened emerge, we supported the unfreezing of my dissociation and enabled the completion of the article.

Embarrassment and Humiliation

Robert Lee and Gordon Wheeler have given to Gestalt a rich theoretical understanding of shame and embarrassment. And from a coaching and consulting perspective, Chris Argyris provides additional insight into the vulnerability/presence dynamic, by noting that, as individuals, we tend to create defensive routines to prevent being embarrassed and potentially humiliated within organizations -- all because, if we admit to being embarrassed, that admission can lead to a sense of humiliation and potentially shame. These defensive routines are referred to as “double binds” in Gestalt, because they create a company culture that is based on a “don’t ask, don’t tell” approach, which eliminates all discussion of critical issues impacting the organization and an individual leader’s performance.

Humiliation, furthermore, tends to emerge when ordinary embarrassment progresses too far, and when it does, the coaching relationship heads down a dark path. Similar to shame, the distinguishing feature is that humiliation evolves from a sense of being “done unto by others” whereas shame, when unraveled is experienced as being “done unto by self”. The importance of this differentiation is that humiliation can result in a projection onto the coach whereas shame will require the coach to support the person to move through and reframe the experience.

Aaron Lazare (1987) sheds some light on the situation. He indicates that the experience of humiliation involves five characteristics: (1) visual exposure, i.e., feeling blemished, exposed, or stigmatized; (2) feeling reduced in size, i.e., feeling belittled, put down, or humbled; (3) being found deficient, i.e., feeling degraded, dishonored, or devalued; (4) being attacked, i.e., experiencing ridicule, scorn, or insult; and/or (5) having a spontaneous avoidant response, i.e., wanting to hide one’s face or sink into the ground4.

According to Klein (1991), humiliation is so powerful that the fear of humiliation is as strong a deterrent for human behavior as the actual experience of humiliation. Merely observing or participating in someone else’s humiliation is enough to stimulate the desire to avoid it. In the most basic terms, to be humiliated is to have your personal boundaries violated and your personal space invaded. The internal experience is that of having something done to you (against your will).

Returning to our opening example for clarification, if I assume that my former client X felt humiliated by me, then his sense of “being done unto” would lead to his action of punishing me by shifting my large contract with his company to another firm. Moreover, the model provided by the presence/vulnerability dynamic provides a glimpse of what happened in that particular indelible moment, which in turn reveals why understanding this dynamic is a critical tool for coaches.5

| 2) Client experienced humiliation by coach’s lack of presence | 1) Client felt close and supported by coach |

| 3) Client disconnects from coach | 4) Client breaks all communication with coach and moves work to another coaching firm. |

Emotions and Maladaptive Behavior

Coaching often involves dealing with repressed emotions or creative adjustments that, in earlier years, may have worked perfectly well. But when problems arise with how a client feels and thinks about his/her habitual ways of behaving, unconscious and maladaptive behavior may be the cause (Izard, 1993). As a result, such behaviors often become the focus in executive coaching.6

Here’s an example: a well-seasoned, executive had been hired to become the CEO of a large utility organization comprised of many small utility companies. Part of the succession process included a five-year process, during which this executive was expected to become acquainted with and understand the entire organization, by serving as president of each subsidiary organization for one to two years. Presiding over the most recent subsidiary, as had happened with all the others, the performance metrics showed improvement. However, in taking a final evaluative step -- before moving this executive into the CEO position of the entire organization -- the board asked for an in-depth review of the candidate executive’s leadership style. They used interviews and a 360 assessment of all five of his temporary or “try-out” subsidiary jobs. What the board found was disconcerting. The review revealed that their candidate was a heavy-handed manager, using command and control behaviors; he was not what they wanted, which was a leader who built relationships and used influence to guide the organization. When confronted with the findings, the candidate acknowledged his command and control style of leadership, but he was absolutely convinced that it wasn’t a problem. In his opinion, his leadership style was the primary reason for his success, to date.

As I was asked to work with this executive candidate, I needed to convey the fact that the board would not promote him to CEO unless his leadership style changed. He quite calmly assured me that the board would most certainly not bypass him based on his leadership style. And he absolutely refused to consider the possibility that, over the long term, his style would lead to a disconcerting reversal of the improved performance metrics, even when solid research supported that inevitable result. I could see that he was perceptually locked into a picture of how to be successful, based on his prior experience. What was worse was that he wasn’t willing to move even slightly into the more vulnerable possibility that he could be more successful if he expanded his leadership skills.

Six months later, another person was promoted to CEO, and the command and control candidate left the organization shortly afterwards, convinced the board had chosen the wrong candidate -- in other words, still refusing to see the limitations of his command and control leadership style.

The Fury of Humiliation

Maladaptive patterns appear to have one common denominator, and that is an underlying fury or rage that stems from the experience of humiliation (Scheff, 1987). This kind of fury is closely related to the all-consuming rage of a frustrated child, or an oppressed individual prepared to “destroy the world” after experiencing years of racial, class, gender, and other forms of discrimination (although helpless to do so). Regardless of whether the rage is turned inward in the form of depression or despair, or outward in the form of vengeful fantasies, paranoia, or sadistic behavior, those who are driven by such fury almost literally consume themselves — and often others — with rage. They deplete their emotional, intellectual, and physical energies, either in attempts to exact revenge, or in vengeful fantasies of somehow undoing the wrong that was done to them (Klein, 1991).

When humiliation-based fury is directed outward, it creates additional victims, often including innocent bystanders -- as is so often the case with command and control leadership styles. When directed inward, the resulting self-hatred renders victims incapable of meeting their own needs, let alone having any energy available to love and care for others. In either case, those who are consumed by humiliation-based fury are absorbed in themselves or their cause -- wrapped in wounded pride and their individual or collective righteousness -- the very epitome of egoistic self-importance. (Returning again to my first example, I can only guess that X, my former client, felt wounded in some way and that this wound is what inspired him to sever our business relationship.)

When I apply the same process to my work with clients, I am often able to foresee when a client is moving into a dangerous dynamic with vulnerability and presence, one which could lead to feeling exposed and, therefore, humiliated. Moreover, depending on the client’s internalized coping mechanisms, s/he might internalize the experience by becoming overwhelmed, leading directly to numbing, or might externalize it in the form of rage s/he then directs at me as coach. The latter has transpired more than enough times in my career that I’ve learned the symptoms and can redirect the client’s energy towards an insight, instead. I accomplish this by reducing the feeling of vulnerability through increasing the intellectual/rational presence of the client.

Overcoming Humiliation and Shame

It can be humiliating, in and of itself, to tell someone that you are feeling humiliated -- and feel powerless, as well, to do anything about it. As coaches, we can support our clients in overcoming humiliation by pointing out that this unexpressed emotion can, in fact, be the very key that will open the door to constructive dialogue. This occurs when shame is separated from humiliation -- by noting that shame is a natural feeling which acknowledges what you have done, whereas humiliation is an unnatural feeling that arises when someone attempts to ridicule or debase you. If the coach functions as a bare witness (as very aware and present-centered), it can be liberating for the client to know someone understands that his/her fury or rage comes from a deeply felt experience of humiliation, hurt, and betrayal that occurred in the past.

To overcome shame in a therapeutic sense requires the complete assimilation of both shaming events and process. While this means transforming those early governing scenes of shame (introjects/shame-binds), it also means moving beyond recovery to develop a recreated sense of self. The presence/vulnerability model provides a means for the client to understand his/her behavioral dynamic, without the coach crossing over into the realm of therapy. The presence/vulnerability model also enables the client to embrace a new vision of self and create a coherent, integrated identity that is fundamentally self-affirming, so s/he no longer needs to engage in maladaptive behavior.

Gestalt Experiment and the

Vulnerability Presence Dynamic

Understanding the broad spectrum of potential responses to feeling vulnerable, and how that may lead to either intimacy or humiliation, we can understand, as well, how the ability of client and coach to stay fully present with the self and other can lead to an insight or a change in behavior. In many cases, by supporting the client in understanding the value of presence – the value of checking in with him/herself on a frequent basis – s/he creates a deeper physical, emotional, and mental awareness. The Contact Model shown in Figure 1 illustrates how we can use the X/Y axis to create the presence/vulnerability dynamic. The upper right hand quadrant (Quadrant 1) is of course where the coach is likely to see the greatest results. If the coach is able to be a present-centered witness and container for the client, by maintaining an awareness of his/her balance between presence and vulnerability -- while also supporting the client in finding some of that same balance -- the potential for successful work can occur, through supporting the client to meet and possibly cross the I-boundary. For example, looking at Figure 1, we can see that it includes descriptions of experiences within that particular quadrant and, as a result, the model begins to come alive. Each quadrant reflects the degree of presence and vulnerability that exists (or is missing), resulting in an internalized point of contact for the client, the coach, and their dyad.

As coaches, we can check in with ourselves and with our clients to get a sense of which quadrant we are residing in, as well as which one we are moving towards. Moreover, with a bit of further probing, the sense of which quadrant our coach-client dyad resides within can be discovered by how far apart coach and client are in relation to one another. Here’s an example: while working with the CEO of a major corporation, I noticed that work had been slow and tedious, with no apparent shifts in the client’s awareness or behavior. While reviewing a company-required 360 feedback report, this CEO wrote that he’d heard all this feedback before, and wasn’t going to alter his behavior this time, either. Holding the edge of my internal anxiety, I asked how not changing had served him. Then, I asked how not using the feedback to change had also not served him.

After voicing his immediate negative reaction, he then asked me to summarize the 360 results and the changes that were being suggested by his board, direct reports, and significant others. When I finished, he maintained steely eye contact with me for well over a minute, before providing a succinct description of what was not working now, and what he needed to begin doing to be effective. I agreed with him and, in his twelve-month follow up, all the changes had been implemented, without regression.

This success was made possible by the fact that I first tested the gap between us by moving further into my sense of vulnerability and listening to and using my anxiety to see what was not being seen by either the client or by me. I then invited this CEO to move out of the story that had not served him, and into a realization of how his story and his unwillingness to change were undermining his leadership.

If the coach creates a safe and balanced container, but is not able to support the client in developing and sustaining a similar balance for him/herself, the client could – in a nanosecond – feel overwhelmed by a flood of vulnerability, thereby pulling him/her into the upper left quadrant, where s/he feels embarrassed and potentially exposed. Here’s another example: working with a different client whose 360 results pierced her stern executive demeanor, I witnessed an emotional outburst. While sobbing, she apologized profusely, bewildered and embarrassed by her emotional reaction, as well as by her tears. This double-bind situation of being embarrassed about being publicly embarrassed held the potential for humiliation. But just as suddenly as it began, her emotional outburst ended and with it went any sign of emotion or embarrassment. This executive had moved to the lower left-hand quadrant, into no vulnerability and no presence. She appeared zoned-out as she excused herself, left the room, and ended the coaching relationship.

In a similar situation, in which a client was visibly moving into a flood of emotion, I asked him why he thought this was occurring. Quickly redirecting his focus, he thought about the answer to my question, and the emotional reaction and feeling of vulnerability began to wane. This happened because thinking is a rational process that doesn’t require vulnerability. As such, my client produced a rational explanation after catching himself in “mid-flood.” By providing a lifeline to him in this way, I was able to redirect the coaching relationship by teaching him the contact model. He began to understand his own sense of presence and vulnerability and how to manage these states more effectively.

It is important to note that, when teaching the client this model, it can be used to either avoid any sense of vulnerability or to manage vulnerability more effectively -- the latter being consistent with true leadership skills. In my experience, there is a tendency toward self-preservation that occurs until the client develops sufficient skill in staying fully present while managing vulnerability in such a way as to be effective.

The final quadrant in the lower right hand corner is where there is no vulnerability and a high degree of intellectual presence. Frequently, this is the area that many senior executives reside within -- often 90% of the time, in fact. It is typically considered evidence of strength to display these traits, and it feels like a safe haven, while also providing protection from any situation that could feel embarrassing or humiliating. Interestingly, the dark or shadow side of this quadrant involves a movement into more vulnerability by passing through the first quadrant (intimacy), albeit briefly. In a nanosecond, the client can swing into the second quadrant, feeling totally exposed. Once this occurs, there can be a moment when all expression seems to freeze, as the person flees into numbness, or the third Quadrant. Occasionally, s/he will stay frozen there. However, many times, s/he will return to the absolute rationality of the fourth Quadrant, beginning to shred the coach with razor sharp intellect. In this case, the client feels humiliated and unleashes his/her fury as a result.

Bringing this back to the Gestalt presence/vulnerability contact model enables us to track the I-Boundary (what is me, and what is not me) for the client, for ourselves as coaches, and in time, for the coach-client dyad. Gestalt experimentation is frequently associated with expanding the individual's I-boundary, as it seeks to draw out and stretch the habitual boundary. Using experimentation, the Gestaltist encourages the client to "try-on" behaviors that feel alien, frightening, or unacceptable -- all within the secure container of the coaching session. "A safe emergency is created, one which fosters the development of self-support for new experiences." (Polster and Polster, 1973) The model creates a structure to support the client in moving through experimentation into new leadership behavior.

Conclusion

The Presence/Vulnerability Contact Model has offered opportunities to deliver helpful insights to my clients, and I’ve seen how it benefits those coaches who studied this model at the Gestalt Institute of Cleveland Coaching Program and applied it in their practices. (As Polster indicates, we create a container for improved connection and therefore new or different meaning-making when we formulate that container which leads to the point of contact.) The coach and client together create a dyadic field which leads to the dynamic of vulnerability/ presence for each other, as well as for the dyad they have created. When the client creates synergy with the coach’s presence, this invites him/her into a new space in which to experiment. When the field is jointly held by both coach and client, the dyadic field then forms a larger container for the presence/vulnerability dynamic to form, and for new insights to emerge.

References

Agyris, C. (1966), Interpersonal Barriers to Decision Making. Harvard Business Review, March-April, pp. 84-96.

Agyris, C. (1977), Double Loop Learning in Organizations. Harvard Business Review, September-October, pp. 115-124.

Agyris, C. (1986), Skilled Incompetence. Harvard Business Review, September-October, pp. 1-7.

Agyris, C. (1991), Teaching Smart People How to Learn. Harvard Business Review, May-June, Reprint 91301, pp. 1-15.

Agyris, C. (1994), Good Communication that Blocks Learning. Harvard Business Review, July-August, pp. 77-85.

Billow, R. M. (2000), Relational Levels of the “Container-Contained” in Group Therapy. Group, 4: 243-259.

Izard, C. E. (1993), Organizational and Motivational Functions of Discrete Emotions. In: The Handbook of Emotions, ed. M. Lewis & J. M. Haviland. New York: Guilford, p. 636.

Kaufman, G. ( 1999), Shame: The Power of Caring. Rochester, Vermont: Schenkman.

Klein, D.C. (1991), Humiliation Dynamic,The Union Institute, http://www.humiliationstudies.org/documents/KleinHumiliationDynamic.pdf

Klein, D. C. (2005), The Humiliation Dynamic: Looking to the Past and Future, http://www.humiliationstudies.org/documents/KleinLookingBackForward.pdf

Latner, J. (1986), The Gestalt Therapy Book. Highland, NY: Gestalt Journal Press.

Latner, J. (1992), The theory of gestalt therapy. In: Gestalt Therapy: Perspectives and Applications, ed. E. C. Nevis. Cleveland: Gestalt Institute of Cleveland Press, pp. 53-56.

Lazare, A. (1987), Shame and humiliation in the medical encounter. Archives of Internal Medicine, 147:1653-1658.

Lee, R.G. (1995), Gestalt and shame: The foundation for a clearer understanding of field dynamics, British Gestalt J., 4:14-22.

Lee, Robert G, & Gordon Wheeler, (1996) The Voice of Shame: Silence and Connections in Psychotherapy, A Gestalt Institute of Cleveland Publication via Jossey Bass.

Lewis, H. (1971), Shame and Guilt in Neurosis. New York: International Universities Press.

Miller, S. (1988), Humiliation and shame. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 52: 42-51.

Naranjo, C. (1970), Present-Centeredness: Techniques, prescription, and ideal. In: Gestalt Therapy Now, ed. J. Fagan & I.L. Shepherd. Palo Alto, CA: Science and Behavior Books, pp. 47-69.

Naranjo, C. (1993), Gestalt Therapy: The Attitude and Practice of an Atheoretical Experientialism. Nevada City, Ca.: Gateways/IDHHB Publishing.

Perls, F. (1969). Ego, Hunger, and Aggression. New York: Random House.

Perls, F. (1976), The Gestalt Approach and Eye Witness to Therapy. New York: Bantam Books.

Perls, F., Hefferline, R., & Goodman, P. (1994), Gestalt Therapy: Excitement and Growth in Human Personality. Highland, NY: Gestalt Journal Press.

Polster, E. (1995), A Population of Selves: A Therapeutic Exploration of Personal Diversity. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Polster, E. (1999), The self in action. In: From the Radical Center: Selected Writings of Erving and Miriam Polster, ed. A. Roberts. Cambridge, MA: GIC Press, pp. 219-237.

Polster, E. & Polster, M. (1973), Gestalt Therapy Integrated: Contours of Theory and Practice. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Scheff, T. (1987), The shame-rage spiral: A case study of an interminable quarrel. In: The Role of Shame in Symptom Formation, ed. H. Lewis. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp. 109-149

Thera, N. (1962), The Heart of Buddhist Meditation. London: Rider

Wheeler, Gordon,(1997) Self and Shame: A Gestalt Approach, Gestalt Review, 1(3):221-244.

Footnotes

1 I have come to believe that one of the driving forces (yearning) in human experience is to establish some form of intimacy with self, other, and the larger world. The cultural lack of support for being fully present -- and for developing conscious vulnerability within this state of presence -- seem to be unintended consequences of an institutionalized drive to create civility and conformity in the fields of education and religion, as well as in for- profit and not-for-profit organizations.

2 Fritz Perls added further clarity when he said, "To me, nothing exists except the now. Now = experience = awareness = reality. The past is no more and the future not yet. Only the now exists."

3 It can be helpful to consider field theory and resonance as part of the sense of containing. It is as if the more present we as coaches become, the more the client is able to move into his/her own sense of presence, creating a safe field for surfacing insights, which is an act of openness often referred to as vulnerability. More will be said about this process in later paragraphs.

4 See Albert Bandura for a perspective on what he calls self-efficacy -- the ability to believe in oneself under any circumstance, and Pauline Rose Clance’s “Impostor Phenomenon.”

5 Donald C. Klein, in his 1991 article, “The Humiliation Dynamic,” adds that

humiliation involves: (1) being put down, as in being “made to eat dirt”; (2) being excluded, similar to acting as if someone does not exist, or made lesser in such as way as to threaten one’s personal integrity and wholeness as a human being; (3) creating a loss of face, so as to damage personal identity and sense of self; and (4) an invasion of the self, wherein all personal boundaries are violated and personal space invaded, such as in a public humiliation.

6 From my own experience, I am aware that my public embarrassment and humiliation in high school was a clear deterrent for me, often leading to immediate dissociation and a form of active inertia that prevented my moving forward with the article editing, until I moved through the old memories and returned to the present, once again.

We Appreciate Your Feedback

Please let us know if you found this article interesting or useful. We will not submit this information to any third parties.