A book by Herb Stevenson, Volume 1. Learn more on Amazon.

Thoughts II:

The Next Step: A Calling

Volume 2 of 3. Learn more on Amazon.

Thoughts III:

Creating The Container

Volume 3 of 3. Learn more on Amazon.

To Lead

Read the article about training with Herb Stevenson in ALN Magazine.

See the article...

Awareness and Emergence:

The Gestalt Approach

to Global Diversity & Inclusion

Herb Stevenson, M.A.

Gestalt Review

Submitted June 1, 2016

Abstract

During the last forty years, members of the Gestalt Institute of Cleveland have created an organizational development (OD) theory by combining Gestalt psychology with Gestalt therapy. Steeped in humanistic psychology, phenomenology and existentialism, holism, field theory, and systems theory, the resulting Gestalt approach to OD has evolved as a present-centered, awareness-building, and high-impact form of intervention. Aside from its unique approach to interventions, its particular core assumptions have led to developing the Gestalt “consulting stance.”

In this article, the core of Gestalt theory and the Gestalt consulting stance, as it applies to organizational development, as well as to diversity and inclusion, will be discussed. Borrowing from the author’s global experience, in which nationalities, ethnicities, and cultural differences converge within one organization, or joint venture, the Gestalt consulting stance (and theory) that supports effective OD interventions, and involves issues of diversity and inclusion, will be illuminated. Finally, using the Gestalt consulting stance, there is an examination of the impact of the ever-increasing size of organizations on diversity. We will see that the migration from international to global organizations, inherently, involves greater diversity. Rather than embracing diversity throughout these organizations, global organizations are clearly diverse and need to become inclusive to be effective.

Herb Stevenson, M.A., is a board certified executive coach, and a faculty member at the Gestalt Institute of Cleveland. He is the CEO of a global gestalt coaching practice, the Cleveland Consulting Group, Inc.

Diversity Versus Inclusion

In the 1990s and early 2000s, diversity was seen as a process for managing the inequities within organizations. Prominent social justice consulting firms like Else Y. Cross & Associates and Kaleel Jamison & Associates (Cross, 2000, Katz et al, 1994) were moving from a model of social justice to one of managing differences. The focus was on how to appreciate differences in the organizational setting, thereby eliminating stereotypes and, hopefully, integrating these differences into the core culture. But it appears that this was more of a transition period focused on building the business case for diversity and less concerned with the actual integration of differences. As organizations progressed over the next 10 to 15 years, however, a second shift occurred, one moving away from diversity management to inclusion. And this seemingly subtle shift from the appreciation of differences to a concern for inclusiveness was actually massive, beginning a process of understanding that globalization meant differences had to be more than appreciated; they had to be fully integrated -- or included within the very core of the organization (Thiederman, 2013; Kaplan & Donovan, 2013; Tapia & Lange, 2015)).

One systemic problem in addressing global diversity and inclusion is the often-unmentioned position occupied by the dominant culture within the diversity spectrum. “To U.S. corporations, diversity is mainly about race, ethnicity, gender, religion, physical disability, age, and sexual orientation. To Europeans, diversity is about national cultures and languages, and it is a reality with which they have always lived” (Bloom, 2002, p. 48). Successful global programs have moved away from enforcing diversity policies and toward inclusion as their driving force -- but it is an inclusion not narrowly defined. Rather, “Inclusion is not just about the obvious differences -- race, gender, ethnicity -– but also different styles of working, sexual orientation, and dress” (Bloom, p. 48). Diametrically opposed to diversity, inclusion does not seek to mold attitudes and behavior; it seeks instead to embrace differences within the confines of an existing national heritage. More specifically, Europeans, Middle Easterners, and Asians “do not feel responsible for the integration difficulties of minority groups living within their respective countries” (Bloom, p.49). The open door policy, for example, that welcomed Syrian refugees seeking asylum in countries throughout Europe, indicates compassion toward the plight of other populations. However, nationalistic values are held as the base line, with the expectation that immigrants will adapt to their new country.1 So these countries tend to focus on embracing differences without diluting their own cultural values. Inclusion, for them, is about differences being accepted within the larger cultural values of their country, without questioning or necessarily reshaping those values. In the U.S., on the other hand, nationalistic values are more often reshaped by diversity policies -- based on the core assumption that the country’s values, and therefore its identity, are both measured against individual rights to equal opportunity and personal expression (thereby perpetuating the “melting pot” of values that has permeated U.S. policy, since the country’s inception). It is the clear difference between these two concepts of inclusion that underscores the effectiveness of Gestalt as an intervention for creating inclusiveness worldwide.

The Organization as Environment

Simultaneous and congruent with the shift from social justice, to diversity management, to inclusion, the exponential growth of organizations over the last four decades has seen the rise of three, still-evolving organizational structures:

- 1. The International Corporation, a nation-centric (for example, the United States, Ireland, Egypt, and so forth) organization that maintains work locations in other countries, and is led by expatriates from that nation who manage local labor.

- 2. The Multinational Corporation, a geographically diverse organization, typically with multiple headquarters around the world, that is often (though less often than international organizations) managed by expatriates, with some inclusivity in lower management positions, but otherwise employing local labor. For example, an Irish company that maintains locations in 38 countries, in which all but a few executive positions are held by Irish executives, and 90%+ of their management positions are held by people from the United Kingdom.

- 3. The Global Corporation, a more inclusive and diverse organization, where diverse nationalities, ethnicities, and cultural differences permeate the organization, far beyond the geographic location of any one worksite, in any one country. Though not a perfect balance of diversity and/or inclusion, it is common for the organization to be managed and staffed by a people from diverse nationalities, ethnicities, and cultural heritages. For example, an Egyptian multi-billion-dollar organization with several sub-corporations around the world was headed by an Egyptian CEO living in Paris, an American COO living in Dubai, and employed people of diverse ethnicities and nationalities throughout its organizational structure. Labor tends to be local; however, it has become more common for an executive from India, for example, to work for a French-owned company located in South America, and there are many similar variations that follow this general model. As the size of organizations grew to exceed $100 billion (Fortune, 2016), their evolution has been from international, to multinational, to still-developing global organizations. A critical aspect of this evolution is that it reveals the developmental stages that occur within organizations as consistent with their executive teams’ willingness to relinquish hands-on control of foreign entities, which is a form of inclusiveness. And this form of inclusivity is accomplished by the creation of “hands-in” control, or by reaching into the depths of these organizations and granting leadership authority that reflects a global mentality, instead of the nation-centric leadership mentality of the past (Ready & Peebles, Tapia & Lange, 2015).

Core Concept

Gestalt psychology underlies Gestalt OD theory, and perception –- and, therefore, awareness – are, as a result, both critical components of this theory. Basically, Gestalt OD changes perceptions and what is, therefore, possible, by supporting awareness to emerge from the existing ground of possibilities and potential. Reality shifts by widening, deepening, and revealing new or alternative ways of thinking, perceiving, and therefore doing (driving and framing perceptions) . According Laura Perls, “Gestalt is [both] experiential and experimental” (Perls, 1992, p. 51). Experiencing contact with diversity and inclusion issues within organizations is like hitting an invisible wall that, in the past, was unmentionable. But experimentation and visceral experience are the means through which a new awareness can arise, and, with it, the prospect of change.

Defining Gestalt

Oddly, the most difficult aspect of Gestalt OD theory has been to translate the word Gestalt from German to English, in addition to translating its various theoretical uses in Gestalt psychology, Gestalt therapy, and Gestalt OD. Christian Von Ehrenfels, who coined the word in the 1890s, used gestalt interchangeably with form. “He insisted that the real essence of any perception was to be found in the Gestalt [in] the immediate experience” (Pillsbury, 1933, pp.484-485). Later on, Gestalt psychologists noted that “experience [and therefore] all truly characteristic phases or processes of mind were just these gestalten or forms” (Pillsbury,1933, p. 485). Though this may seem like complex and potentially circular thinking, the gist of gestalt formation is that we make meaning when creating perceptions while interacting with the outside world, as well as when engaging memories spontaneously as we look inward, in order to understand how an experience has impacted us in the present. As a result, how we perceive and make meaning, individually and organizationally, is endemic to who we are and what we are therefore willing to do. For example, the shift from social justice (inequities of humanity) to diversity management (appreciating differences) to inclusion (seeking value in skills and capabilities) are shifts in meaning making. Hence, a perceptual shift has been occurring for the last three decades. Applying this to a specific client example, a multinational organization had U.S. expatriates in all its senior leadership positions, with the highest-level position for a non-U. S. citizen stopping at the middle-management level. When I approached their leadership about the resulting under-utilization of talent, the CEO thought my perception was ludicrous because, he reasoned, if he were to grant more power and authority to local managers, he would lose control. When I then proposed an experiment, a test case in one country only, he simply dismissed the idea and refused to try it.

Where We Come From

The significance of gestalt formation is that prior knowledge greatly influences our current perception and memory, so that when we remember something, we are reconstructing our perceptions of that event. “All experience and learning that has been fully assimilated and integrated builds up a person’s [or organization’s] background.[This background] gives meaning to the emerging gestalten, and thus supports a certain way of living on the

boundary with excitement. Whatever is not assimilated, either gets lost or remains a block in the ongoing development [or growth]” (Perls, 1992, p. 54).

Gestalt psychology principles of perceptual organization reveal how we form perceptions and how, as a result, we make meaning -- based on our existing knowledge and way of making meaning from experience. But if we are able to witness our own meaning-making process, such witnessing can be invaluable when looking for patterns or themes that remain unconscious for us in our culture and in us as individuals living within that culture. By the same token, understanding the biases and hidden perceptions that prevent greater inclusion within organizations is naturally critical to organizational development. Here, then, are five Gestalt principles of perceptual organization:

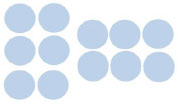

1. The Principle of Similarity suggests that similar items tend to be grouped together, regardless of whether or not the similarity or relationship actually exists. In the image to the right, most people see vertical columns of circles and squares. However, as in much of life, this basic principle is how we develop shortcuts that lead to such things as stereotypes. Without taking the time to determine if there is truly an identical trait, instead of just a similarity, we lose much of our ability to discern what is perceptually occurring. In the U.S., this is often how simplistic perceptions reveal the separation and differences among races, thereby losing the value of individual differences within racial similarities. The most common example of this is that terrible pejorative phrase, “They all look the same,” when one race refers to and dismisses another by, for instance, addressing skin color alone, with no acknowledgment of individual physical differences.

1. The Principle of Similarity suggests that similar items tend to be grouped together, regardless of whether or not the similarity or relationship actually exists. In the image to the right, most people see vertical columns of circles and squares. However, as in much of life, this basic principle is how we develop shortcuts that lead to such things as stereotypes. Without taking the time to determine if there is truly an identical trait, instead of just a similarity, we lose much of our ability to discern what is perceptually occurring. In the U.S., this is often how simplistic perceptions reveal the separation and differences among races, thereby losing the value of individual differences within racial similarities. The most common example of this is that terrible pejorative phrase, “They all look the same,” when one race refers to and dismisses another by, for instance, addressing skin color alone, with no acknowledgment of individual physical differences.  2. The Principle of Pragnanz (simplicity and conciseness) suggests that our sense of reality is organized into the simplest form possible, by eliminating what is unfamiliar or does not seem useful. Hence, we filter out a lot of data that could change how we experience (and as a result, perceive and make meaning). For example, in the figure at right, we typically see a series of circles that suggests the Olympic symbol, instead of many geometric figures. This same process occurs when we quickly make meaning after a quick glimpse, such as the manner in which racial profiling is confused with true investigative processes. Or, assumptions are made about an individual that are based on personal beliefs about a racial group. Often, these events are portrayed around differences of appearance -- the fear that all Muslims are terrorists, for example, or that all black youth who wear hoodies are violent

2. The Principle of Pragnanz (simplicity and conciseness) suggests that our sense of reality is organized into the simplest form possible, by eliminating what is unfamiliar or does not seem useful. Hence, we filter out a lot of data that could change how we experience (and as a result, perceive and make meaning). For example, in the figure at right, we typically see a series of circles that suggests the Olympic symbol, instead of many geometric figures. This same process occurs when we quickly make meaning after a quick glimpse, such as the manner in which racial profiling is confused with true investigative processes. Or, assumptions are made about an individual that are based on personal beliefs about a racial group. Often, these events are portrayed around differences of appearance -- the fear that all Muslims are terrorists, for example, or that all black youth who wear hoodies are violent 3. The Principle of Proximity (contiguous) suggests that objects near each other tend to be grouped together, whether they’re in relationship or not. Hence, the solid circles to the right tend to be grouped into two groups: one comprised of two vertical columns, and the other comprised of two horizontal rows. But, in fact, we do not know their relationship, unless we explore more data. In OD, the familiar phrase, “can’t see the forest for the trees,” is used to describe how someone perceives a situation myopically, or with no larger or contextual perspective. For example, when members of a minority group sit together in a lunchroom, stereotypical reasoning may be projected onto that group -- with no consideration of the fact that they’re all friends, or that this group is no different than a cluster of White people sitting together to eat lunch and socialize.

3. The Principle of Proximity (contiguous) suggests that objects near each other tend to be grouped together, whether they’re in relationship or not. Hence, the solid circles to the right tend to be grouped into two groups: one comprised of two vertical columns, and the other comprised of two horizontal rows. But, in fact, we do not know their relationship, unless we explore more data. In OD, the familiar phrase, “can’t see the forest for the trees,” is used to describe how someone perceives a situation myopically, or with no larger or contextual perspective. For example, when members of a minority group sit together in a lunchroom, stereotypical reasoning may be projected onto that group -- with no consideration of the fact that they’re all friends, or that this group is no different than a cluster of White people sitting together to eat lunch and socialize. 4. The Principle of Continuity as indicated in this illustration captures the fact that the trend lines beside the dots follow the smoothest path -- suggesting by analogy the tendency to develop lines of thought by following preconceived paths of meaning-making. (In this figure, this phenomenon occurs when we see a trend of motion, and decide to follow one trend that is upward, or follow another trend that is downward.) A common example of this principle is the way corporations tend to stick to “the tried and true,” by sending expatriates all over the world to manage strategic business units, never considering that local talent is capable of managing local workers.

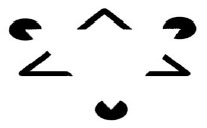

4. The Principle of Continuity as indicated in this illustration captures the fact that the trend lines beside the dots follow the smoothest path -- suggesting by analogy the tendency to develop lines of thought by following preconceived paths of meaning-making. (In this figure, this phenomenon occurs when we see a trend of motion, and decide to follow one trend that is upward, or follow another trend that is downward.) A common example of this principle is the way corporations tend to stick to “the tried and true,” by sending expatriates all over the world to manage strategic business units, never considering that local talent is capable of managing local workers.  5. The Principle of Closure suggests that objects grouped together are seen as a whole, such that things grouped together complete a whole that might, in fact, not exist. We fill in the gaps. For example, in the image to the left, there are no triangles or circles, yet our minds fill in the missing information to create familiar shapes and images. Television has portrayed this principle in numerous movies about a victim experiencing a serious violation to his or her person, typically involving racial or other differences. For example, the fear that all Muslims are terrorists, or that all black youth in hoodies are violent. Unable to distinguish new situations that present no danger -- only that someone “threatening” is approaching -- that person screams in fear. In OD, we find similar closures in how organizations respond to new situations and immediately respond as if it is identical to past experience (for example, in confronting economic downturns). However, in global organizations, combining the Principle of Closure with the Principle of Pragnanz, a false sense of security evolves, by assuming that expatriate leadership understands how to motivate workers with different nationalities, ethnicities, and/or cultures, by applying homeland motivations that work at home. (An example is presented later on, in which a South African’s approach to conflict was misunderstood by Irish leaders, who interpreted his behavior with their own culture’s expectations.)

5. The Principle of Closure suggests that objects grouped together are seen as a whole, such that things grouped together complete a whole that might, in fact, not exist. We fill in the gaps. For example, in the image to the left, there are no triangles or circles, yet our minds fill in the missing information to create familiar shapes and images. Television has portrayed this principle in numerous movies about a victim experiencing a serious violation to his or her person, typically involving racial or other differences. For example, the fear that all Muslims are terrorists, or that all black youth in hoodies are violent. Unable to distinguish new situations that present no danger -- only that someone “threatening” is approaching -- that person screams in fear. In OD, we find similar closures in how organizations respond to new situations and immediately respond as if it is identical to past experience (for example, in confronting economic downturns). However, in global organizations, combining the Principle of Closure with the Principle of Pragnanz, a false sense of security evolves, by assuming that expatriate leadership understands how to motivate workers with different nationalities, ethnicities, and/or cultures, by applying homeland motivations that work at home. (An example is presented later on, in which a South African’s approach to conflict was misunderstood by Irish leaders, who interpreted his behavior with their own culture’s expectations.)

The value of these principles of Gestalt perceptual organization exists in their illustration of the way we take shortcuts -- when using our historically familiar past and our desired future -- to frame our perceptions, in any given moment, of what we are seeing and using to make meaning. As a result, our generally unconscious use of the principles of perceptual organization, as part of our ongoing gestalt formation, will likely be guided by our individual or our organization’s sense of development and path to survival. The question that then becomes relevant for the individual, or the organization, is this: Are our perceptions real? Or are they previously formed fixed gestalts? Real perceptions require the ability to be fully present, and to test any assumptions that permeate our perceptions. Because so much of perception has become habitualized, we tend to create fixed perceptions. These in turn become a fixed gestalt, when we add emotional reactions and beliefs to our perceptions of past experiences as factual and universal. And, more importantly, what can we do as OD consultants to create more awareness about perception formation, with regard to diversity and inclusion? As we shall see, experimenting and experiencing the limitations of perceptual formation regarding differences and inclusion, can be powerful interventions.

Conceptual Theory

Figure/Ground

Figure/ground is one of the core concepts of perception in Gestalt theory. It describes the "emergence, prioritizing and satiation of needs . . . and is the basic perceptual principle of making the whole of human needs or experiences meaningful" (Clarkson, 2000, p. 6). Figure is the focus of interest—an object, a pattern, a behavior—for which ground is the background, setting, or context. The interplay between figure and ground is dynamic and ongoing. The same ground may, with differing interests and shifts of attention, give rise to different figures. Or, a given complex figure may itself become ground, in the event that some detail of its own emerges as figure (Perls, Hefferline & Goodman, 1971, p. 25). Our attention shifts from one figure of interest to another, and when we are no longer interested in one figure, it recedes into the ground and is replaced by another (Polster & Polster, 1973). The thoughts we experience as idle and free-flowing, for example, echo the flow of figures moving in and out of the ground that is the conscious mind. If we wish, these figures can become more fully formed, brought completely into awareness, by attending to them more vigorously. For example, an OD consultant forms figures from the ground of years of experience, multiple theories (including cultural biases), and personal memories to determine what to pay attention to, in relation to the client system. This applies, more directly, to whether or not we have been exposed to broader experiences of diversity and inclusion. One’s own self-review of perceptual patterns is critical to the process of creating successful OD interventions, especially with executive leadership.

As noted above in the Gestalt Principles of Perceptual Organization, an important characteristic of perception is the tendency toward meaning-making; that is, toward identifying a figure we can easily comprehend. Provided data, we will instinctively try to make meaning of it, or create some sense of understanding or familiarity. If we fall prey to any of the principles of perceptual organization, we will create a figure—what to pay attention to—based more on our creative application of prior experiences than on the data and information directly available to us in the moment. Hence, as indicated earlier, the perceptual organization of U. S. corporations’ diversity policy forces policies onto foreign nationals that are inconsistent with their countries’ cultural values.

The ground, on the other hand, does not incite movement towards meaning-making and figure formation. The ground is generally considered unbounded and formless, but it provides the "context that affords depth for the perception of the figure, giving it perspective but commanding little independent interest" (Polster & Polster, p. 30). Ground evolves from our past experiences, from our unfinished business, and from the flow of the present experience. In a sense, one's entire life forms the ground for the present moment. The past and the present color the variety of the individual's closed and unclosed experiences: "All experience hangs around until a person is finished with it," the Polsters insist. Although individuals can tolerate the internal existence of a number of unclosed experiences, the experiences themselves, if they become compelling enough, will generate "much self- defeating activity," and will essentially demand closure (p. 36). For example, the unwritten rules of most organizations surrounding diversity and inclusion are considered unfinished business within a Gestalt framework. Because no one directly addresses the unwritten rules of how to deal with diversity and inclusion, they become part of the “unfinished business” that circulates throughout the organization’s culture. This has led to diversity policies congruent with the U.S. cultural values regarding individualism.

But once closure of an experience has been reached -- either through a return to old business, as in, “that’s the way we always do things around here,” regardless of the facts, or by relating a past experience to the present -- "the preoccupation with the old incompletion is resolved and one can move on to current possibilities" (Polster & Polster, p. 37).

But once closure of an experience has been reached -- either through a return to old business, as in, “that’s the way we always do things around here,” regardless of the facts, or by relating a past experience to the present -- "the preoccupation with the old incompletion is resolved and one can move on to current possibilities" (Polster & Polster, p. 37).

Change is a function of closing out one experience and moving on to "current possibilities.” As such, Gestalt has a high regard for "novelty and change [and] a faith-filled expectation that the existence and recognition of novelty are inevitable, if we stay with our own experiences as they actually form" (p. 48). It is in the novel that we realize how much of organizational life has not already happened, as a large portion of the daily thought revolves around anticipated actions for self and others. But the only thing that really matters -- if we wish to ensure clear perception -- is to stay fully present in the here and now, and see the facts as they actually exist, without the tendency to obscure reality with some form of perceptual organization. For example, as gender biases become uprooted and, as a result, more clearly revealed, micro-inequities may tend to develop, in order to hold those biases in place. For instance, when a man is assertive at work, he is perceived as being “a strong leader”; when a woman is assertive at work, she is perceived as being “a bitch.”

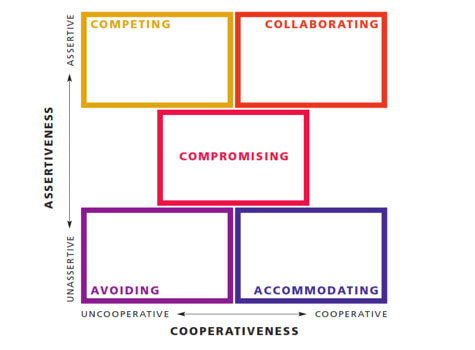

An Example of Reframing

Working with a predominantly White European leadership team, the focus for the first week of a three-week training program was on individual awareness, and so the team completed assessments yielding an in-depth sense of self that they’d never been exposed to before. (One leader said the resulting 60 pages of information concerning his personality preferences, conflict style preferences, and interpersonal relations preferences provided more information than he cared to know.) During the course of self-revelations through awareness, one exercise asked the team to place themselves within a grid of five conflict styles. The grid revealed degrees of assertiveness versus degrees of cooperation, which then translated into five categorical preferences for dealing with conflict–competitiveness (high assertion, low, or no cooperation); collaboration (high assertiveness and high cooperation); compromise (medium assertiveness and cooperation); avoidance (no assertiveness and no cooperation); and accommodating (low assertiveness and high cooperation). When the team settled into their places on the grid, most were standing in high assertiveness and low cooperation as their preferred conflict style. But the single South African leader was standing in avoidance and a leaning toward cooperation. When I asked the team how they interpreted their conflict style placements, the majority thought conflicts were competitive and should to be won with passion and anger (they also expressed this opinion with a significant amount of bluster and great pride). When I asked the team how they interpreted the conflict style of the one South African, they said that he “lacked backbone,” a quality they’d been taught to value as kids. When asking the South African to interpret his conflict preference, I also asked if he shared my cultural view as a Native American that to be highly assertive was disrespectful, an attack on another person’s spirit. The South African immediately said yes, and told several stories about his cultural upbringing, living under Apartheid. When he finished, I asked the rest of the team if their perceptions about this teammate had changed -- and if so, how? The majority now understood how nationality, ethnicity, and cultural differences influenced their meaning-making concerning others. When this lesson was extended to how each leader would engage with one another in the future, there was clear recognition that conflicts would be resolved more quickly via collaboration when working with the South African. When asked about each leader’s direct reports (which included people from the Middle East, eastern and western Europe, and Asia), the conversation turned to the way conflict styles are impacted by nationality, ethnicity, and culture, and how understanding and appreciating these conflict-style differences were imperative to effectively leading and motivating their people. This also reflects how reframing can change the figure-ground formation influenced by habitualized perceptual formation.It is similar to that often-used illustration, in which an image can either be seen as a goblet or as two people facing each other, depending on how the viewer’s mind organizes the data. The same type of figure/ground formation occurs when addressing diversity and inclusion issues. As a result, the Gestalt consultant must constantly look for opportunities to reframe existing perceptual formations.

Kenneth W. Thomas and Ralph H. Kilmann, (2007) The Thomas Kilman-Kilmann conflict Mode Instrument, Palo Alto, Ca. CPP, Inc. , p 2.

Paradoxical Theory of Change

At the center of Gestalt OD theory is the paradoxical theory of change, which is the touchstone and guiding principle for most Gestalt interventions. However, to fully appreciate the paradoxical theory of change, there needs to be an acknowledgement, as suggested by Duncan and Miller, that “within the client is a uniquely personal theory of change waiting for discovery, a framework for interventions to be unfolded and utilized for a successful outcome” (2000, p.180). This "uniquely personal" approach to change supports what is known in Gestalt therapy as the paradoxical theory of change—in which it is assumed that change occurs when an individual, group, or organization acknowledges and accepts what he, she, or it is, rather than continually trying to be what he, she, or it is not. In other words, “Change does not take place by trying coercion, or persuasion, or by insight, interpretation, or any other such means. Rather, change can occur when the [client] abandons, at least for the moment, what he [or she] would like to become and attempts to be what he [or she] is” (Beisser, 1970, p. 77). It is in the fullness of this state of being that fixed gestalts dissolve, and greater complexity can be seen and utilized as part of the “what is.” For example, an organization capable of realizing that “the emperor has no clothes,” will also be capable of eliminating the fixed gestalt and unwritten rules about “how we do things here” -- to clean their perceptual lens, so the facts can be seen as they truly are. It is in the details of the here and now that insights and, therefore, the changes needed for organizational development success, exist (Stevenson, 2010).

Applying the paradoxical theory of change to global diversity and inclusion, the focus becomes to support the organization in allowing something that already exists to emerge and be seen. In the U.S., diversity issues (or injustices) are often revealed during a crisis. Texaco, for instance, was forced into a consent decree by the Department of Justice when blatant discriminatory behavior was recorded during an executive meeting. Though initially perceived as an act of government coercion, the impact over time was a recognition and acknowledgement of the company’s discriminatory behavior, which resulted in a complete revision of corporate values and behavior (Williamson, 2002), and led to the evolution of more effective diversity policies and procedures.

Intercultural Conflict

In a global environment, efforts to increase diversity through compliance alone do not work.

As highlighted earlier on, Europe already perceives itself as diverse, and is therefore not interested in U. S.-centric policies and enforcement procedures. The Gestalt consultant will, as a result, need to create ways of incorporating national values that can be used to highlight hidden values lurking within inclusive practices designed to embrace a diversity of peoples.

For example, some years ago, there was a marked increase within a large city park system in the U.S. of critical incidents involving park rangers policing the beaches and park as a whole. The prevailing belief among rangers was that park visitors were now more aggressive and less respectful of authority. But an on-site assessment uncovered the fact that many of those enjoying the park were immigrants from several different countries. Beaches and picnic areas were being used for immigrant group and family gatherings. (My own experience with these beaches was one of enjoying the melody of multiple languages and laughter, as food was shared among those gathered there.) During the review of assumptions, the park rangers had an authoritarian perspective, anxious that “respect for the law” be observed. They were uncomfortable with passionate conversations about the appropriateness of various behaviors, and perceived them instead as disrespectful. When the team joined these perspectives with the differing cultural values of a representative group of these immigrants, it led to the insight that different cultures respond to authority in different ways -- especially when discussing behavioral appropriateness (specifically, a loud gathering that was annoying to nearby non-immigrant groups).

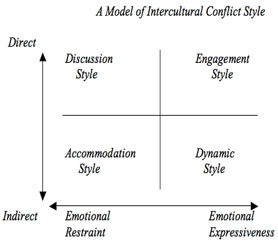

We then used an intercultural conflict instrument to highlight cultural differences by measuring the degree of direct -- versus indirect –- approaches, and emotional restraint versus emotional expressiveness. Because the assessment revealed common behavior driven by the cultural values of different countries, we were able to show that the immigrants were simply behaving in accordance with their core/cultural values.

As can be seen in the figure below, each country has a typical behavioral style. By redirecting the rangers’ attention away from compliance and toward embracing different cultural styles, their attention was refocused on being more relational and inclusive. Their initial action would now be to determine the country of origin; once determined, the rangers would approach the group according to their likely engagement style. Not all that surprisingly, the number of escalating conflict incidents was soon significantly reduced. Their heightened awareness of cultural differences and shift in perceptual order, meant working with differences as a means to a common goal -- versus imposing their own authoritarian cultural values, in order to force compliance.

Figure 1: Intercultural Conflict Styles

Direct & Emotional Restraint = Discussion (Talk At) USA & Canada Eurocentric: Great Britain, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Germany; Asia Pacific: Australia & New Zealand |

Indirect & Emotional Restraint = Accommodation (Talk About) Native American; |

Direct & Emotional Expressive = Engagement (Talk With) African American; Euro: France, Greece, Italy, Spain; Central/Latin America: Cuba, Puerto Rico; Asia; Russia; Middle East: Israel |

Indirect & Emotional Expressive = Dynamic (Talk Around) Arab, Mid East: Kuwait, Egypt, Saudi |

Adapted from Intercultural Conflict Style Inventory, developed by Mitchell R. Hammer, www.icsinventory.com p.15

Core Assumptions

Over the last forty years, Gestalt theory has formalized a number of core assumptions with regard to OD theory for the application to individuals and organizations. This comparative explication is outlined below, in Table 2

| Individual Development | Organization Development |

Learning occurs through examination of here and now experience. Awareness is the precursor to effective There is an inherent drive for people to Growth is facilitated by the interaction of Growth occurs at the contact boundary, Experimentation with new forms of Change is the responsibility of the client, not the consultant. Individual autonomy is crucial to healthy adjustment. |

Learning occurs best through focusing on the Change in systems occurs only if members of People in organizations have the potential for A climate of openness and trust is essential The feedback/action research model is the Pilot studies and experimentation are a critical source of learning. Change is the responsibility of the client, not the consultant. The small group is a highly effective unit through which to bring about change. Change at one level of the system permeates all other levels of the system. |

Table 2: Core Assumptions of Gestalt OD Theory

for Individuals and Organizations

Modified with permission from Edwin Nevis, Organizational Consulting: A Gestalt Approach, 1997, p.112

Levels of System

Gestalt as a holistic theory posits that, for every OD conflict, problem, or situation, there are multiple levels of system. For example:

- Intra-personal—consciously or unconsciously, what and/or how I think, in relation to different life situations (often referred to as the stories that I carry from all my life’s experiences). Perceptions and contact are made with myself.

- Inter-personal—consciously or unconsciously, what you and I respond to and/or how we respond to each other. Perceptions and contact are made in how and where we meet each other, the point of exchange between us, as well as individually.

- Small group—consciously or unconsciously, what we choose to respond to and how we choose to respond to each other -- or to the conflicts, problems, or situations of the group. Perceptions and contact are made at the group level, even though the intra- and inter-personal levels are being engaged simultaneously.

- Organization—consciously or unconsciously, what we as an organization choose to respond to, and how we choose to respond to each other, or to the conflicts, problems, or situations within the organization. Perceptions and contact are made at the organizational level, even though the intra- and inter-personal, as well as the group level are being engaged simultaneously.

From a Gestalt OD perspective, we can examine how the levels of system relate to each other when applied to the above example of the park rangers, which yields the following realizations:

- Each level of system contains the conflict, problem, or situation in its entirety. It can be dealt with individually, as was the case for the park rangers’ assumption that each incident was an act of insubordination.

- Each level of system can influence all other levels of system. Recognizing the rangers’ culture (rules of engagement as a U.S.-centric organization), we chose to look at how national (cultural) values permeate behavior and perceptions, and could therefore impact this and future engagements.

- For the conflict, problem, or situation to be completed, all levels of system must explicitly address the issue. By intervening through highlighting differences, and approaching the solution based on inclusive practices, we were able to shift the park rangers’ (their organization’s) perceptual formation.

The power of taking into consideration multiple levels of systems is the way it enables the Gestalt OD consultant to look through the organization’s dynamics and determine the most effective points of intervention. For example, highlighting the unwritten rules of an organization may fall on deaf ears, if unilaterally indicating that the rules are bogus -- something that has generally often happened with regard to diversity and inclusion interventions. The Gestalt OD consultant could test the waters for an initial intervention with the CEO or a group of senior executives, in order to create new awareness about how the unwritten rules serve, or do not serve, the organization. Such an intervention seeks to eliminate the perceptual organization that has perpetuated the unwritten rules in a self-sealed form, making them unavailable for examination.

In another situation, I was part of a team of Gestalt colleagues, several of whom were diversity professionals with years of experience, and we were charged with providing a training program on teams and small group dynamics. Our team included four White women, a man from Ghana, a Native American man (myself), and a white man. As the program’s design began to take shape, three of the seven formed a subgroup that took control of the design process. Initially, this was not bothersome, as it appeared that we were still a team. But as things progressed, the subgroup took over training responsibilities for three of the five planned weekend sessions. The two exceptions were hour-long presentations assigned to myself, the Native American, and the team member from Ghana, scheduled during the third weekend. During these presentations, we were supposed to represent how “our people” would approach team dynamics. This felt like tokenism to me. After all, I had more experience in organizational team dynamics than any member of the subgroup, yet I was being asked to limit my contribution to a talk about “my people.” So I asked several other team members if they saw this situation as I did, and they concurred that it seemed like tokenism (discrimination slightly disguised), but they did not want to either name it or deal with the subgroup on this topic. This backing-away felt to me like nothing less than an invalidation of my very existence; an existential crisis ensued, during which I saw how this experience had silenced my voice within the group.

For weeks, I struggled to determine my best course of action. Finally, I realized that since the participants were a mix of Black, White, Asian, and biracial, I could use my biracial background as a frame of reference to teach the difference between how White corporate Americans and Native Americans would solve this problem. Corporate Americans are often expected to suck it up and take one for the team. As a Native American, my expectation was quite a bit different. In Indian culture, the belief is that there’s something wrong with the community if such a divisive subgrouping occurs and is allowed to lead the group. As a biracial American, furthermore, this kind of experience is crazy-making, because of the resulting cultural confusion regarding what to feel and how to act—am I white or am I red in my racial identity.

But my attempt at using this situation as a teaching moment was received with mixed reviews. The three White faculty members were enraged, and the White participants were embarrassed, but the Asian, Black, and biracial participants were grateful that I’d named the differences, revealing how they can cause deep cognitive and emotional dissonance. Later on, the subgroup team tried to chastise me publicly for teaching these dynamics in the class, though they admitted everything I said was true and had, in fact, occurred. For me, it was a clear example of how unconscious group discrimination occurs, and how the offending group -- or subgroup, in this instance -- will move from a group level of system to an individual level of system, once brought to conscious awareness.

For example, the subgroup’s reaction prevented them from seeing the larger dynamic of their behavior, creating a barrier to eliminating their discriminating behavior. More specifically, when a group dynamic occurs, the initial discriminating act creates humiliation in the target group that invokes an invalidating process, a shame-like experience of not deserving to exist (see Donald Klein’s work on shame and humiliation). But if able to recognize the invalidation as other-created, it is then possible to overcome it. Otherwise, it just becomes another social shaming experience. In this case, it took me several excruciating weeks to muster the courage –- or the desperation -- to address this issue obliquely through a teaching process. Remember, though, that no group support existed to correct the dynamic prior to my token hour of teaching.

When I was able to overcome the humiliation caused by the subgroup’s behavior and name the act, the situation became quite convoluted and complex. First, I chose to breach the American and, commonly, corporate social contract of not naming such acts of humiliation. Second, my breach led to the potential for an embarrassing and shameful experience for the offending group (see Chris Argyris’s work). Third, if the offending group had been able to stay present and experience the naming process, including the inappropriateness of the behavior, tremendous insights could have occurred that would lead to new awareness and behavior. Fourth, if the offending group, like this one, cannot stay present for the naming experience, personal shame may result which will lead to some becoming enraged. Fifth, when this defense results, it is common for the offending group to project their involvement and responsibility for the situation onto the original source -- onto me, in this case -- to further humiliate by acting as if the entire process was the fault of the originally spurned group (this is of course what occurred in this unfortunate situation).

What I learned from all this was that I need to be clear at the start about my expectations when working with groups. Not voicing them puts me in compromised situations, in which the team might not be able to address unconscious and unintentional acts of humiliation. Furthermore, I assumed that this team was beyond unconscious acts of discrimination because of their individual diversity training, but that was extremely naïve (after all, we live in a country in which each group wants “us” (versus them) to dominate, while unconsciously excluding “the other” racial groups).

Gestalt Consulting Stance

The Gestalt consulting stance has evolved as a consummation of Gestalt OD theory. It includes the core concepts that permeate Gestalt OD practice, while codifying that practice as a stance to be taken by the OD practitioner, and it is especially useful and important for the Gestalt consultant working with issues of diversity and inclusion. Figure 3 profiles each aspect of the Gestalt consulting stance. Its three major themes are: Use of Self as an Instrument; Providing a Presence, Otherwise Lacking in the System; and Basic Activities of Gestalt Consulting (Which Require Attending to All Levels of the System, Including Yourself). To embrace these themes in my introduction to global clients, I started collecting data about my reactions, gathered while traveling to various parts of the world as a consultant, versus my years spent as a U.S. Marine, four decades earlier. ( I realized the lack of familiarity of different cultures versus the actual experience was a totally new perception for me.) Moreover, I understood that I was becoming part of a group (a corps) of world travelers who move among countries the way other consultants move among states. As a result, I took on the task of understanding cultural differences, in order to navigate more easily from country to country (including whether to make direct eye contact with immigration officials in certain countries).

FIGURE 3: A Profile of the Gestalt Consulting Stance

A. Use of Self as an Instrument:

- 1. You must become an awareness expert

2. There should be congruence between your behavior and what you want to teach others

B. You Provide a Presence, Otherwise Lacking in the System:

- 1. Stand for certain values and skills

2. Model a way of solving problems, and of dealing with life in general

3. Help to focus the client's energy on the problems, not the solutions you prefer

4. Teach basic behavioral skills

5. Evoke conditions that enable experimentation

C. Basic Activities of Gestalt Consulting Require That You:

- 1. Attend, observe, and selectively share observations about what you see, hear, and feel

2. Attend to your own experience (feelings, sensations, thoughts, etc.), and selectively share these experiences, establishing your presence while you do

3. Focus on energy in the client system (and the emergence or lack of themes or issues for which there is energy), thereby supporting a mobilization of energy so something happens

4. Facilitate clear, meaningful, heightened contacts between members of the client system (and with you)

5. Support the client system to complete Units of Work, and to achieve closure around unfinished business

Bringing What’s Missing through Awareness

The Gestalt consulting stance requires having the self-awareness to see what is missing in the system, and the courage to bring that behavior or insight into the organization. For example, when participating in a roundtable discussion about hiring minorities at a Society of Human Resource Management conference, there was an African-American, a Latino (Hispanic), a Caucasian Ageism expert, and myself. Throughout these roundtable discussions, all participants referred to one another with an appropriate level of respect and inclusivity. Not once were Native Americans referred to as a subordinated group, and neither was I referred to as a Native American member of the panel.

So when I spoke, I talked about this experience -- by way of illuminating how Native Americans are outside the general awareness, even of other subordinated groups -- and, in particular, of HR hiring specialists. I was careful to emphasize that I did not find this oversight malicious, but did find it dismaying that Native Americans did not exist within everyday awareness for most Americans. I spent the rest of the session offering information about Native American graduation rates, the percentage of graduate degrees, and how to find Native American job applicants (it was gratifying that several HR attendees later asked for more information along these lines).

In another situation, I was hired by a college president to work with him for a year on enhancing his leadership skills, and then on enhancing his effectiveness with his direct reports. After that, in the second year, we would work to enhance the leadership skills of his direct reports. I was excited because he was well-published on diversity issues, and the college supported an annual symposium on religious diversity.

As we parted, we agreed that we would jointly announce the coaching plan to his team. Instead he chose to meet with his direct reports without me to announce our work plan without me. After this college president chose to override our agreement and share the project with his team, they did an internet search and found my native American website. As a result of their search, they found the words, “shaman” and “shamanism” (see my Native American website: www.onewhitehorsestanding.com). Meeting as a group with this president, they informed him that being associated with me would destroy his career. Clearly, they said, shamanism was heathenism, at best, and Satanism, at worst. My would-be client bought their fear-based arguments and called me, conveyed their concerns, and ended by saying he had decided to support his team’s findings and protect his reputation.

I said it was intriguing he was advocating religious bigotry, because the literal meaning of “shaman” is holy one, and shamanism is a collection of nature-based spiritual practices. He was not pleased that I questioned his logic and his decision, asserting that he was not a bigot and his act was not religious bigotry. In the end, he chose to attenuate his fear of looking bad. Subsequently, I wondered what he might have learned during our executive development process about his own inability to be inclusive.

Experiment

A critical aspect of Gestalt OD is being able to experiment with new ideas, experiences, and perceptions. By definition, change cannot happen unless an intervention occurs -- through some form of insight that creates new thought or behavior. The basis of Gestalt experiment (or pilot studies) is that "all living systems start small" (Senge, 1999, p. 39). Organizational experiments are small-scale tests, in which new business directions are explored experimentally -- at far less cost to the organization than the actual implementation of an untested and large-scale new direction. Experiments can vary widely -- from impacting an individual, to completely shifting the working paradigm of the organization (Tomke, 2001). Diversity and inclusion both require awareness-building experiments, in order to create new ways of thinking and framing the organization’s effectiveness in completing their mission.

The benefit of an experimental approach is that all outcomes are seen as valuable. Experiments reveal potential new ways of thinking and behaving that could provide significant insights into organizational courses of action. Examples would be insights that support a CEO's strategies to stop unconscious and undermining behaviors, help a team redirect its energies, or guide the organization in deciding whether to shift its focus from enforcing diversity policies to embracing diversity through inclusion policies and management practices.

Over the last five decades, Gestalt experiments have often been referred to as "creating a safe emergency," wherein the client is given the opportunity to try something new and untested, in order to find out what is or is not desirable and possible. Such experimentation is valid at all levels of system -- the individual, the group, or the organization. In the safety of experimentation, the client is able to adopt a new behavior, or a different way of conceptualizing a problem or situation, without risking personal or organizational resources. An awareness of what is possible leads to an awareness of "what might be." That is, how things could be different (and better) in the future.

Obviously, shaping and supervising successful experiments calls on particular knowledge and skills. The nature of the experiment depends upon the client's specific needs, situation, and environment. Fashioning an appropriate experiment is a highly creative process. And, according to Zinker, this process is designed to reach certain goals, as outlined below:

Goals of Creative Experimentation

(ADAPTED FROM ZINKER, 1977, P. 126)

- To expand the range of behavior for the individual, group, or organization

- To create conditions under which ownership of specific behavior by the individual, group, or organization can be claimed

- To stimulate experiential learning from which new self-concepts can evolve

- To reveal creative adjustments that have resulted in unfinished situations

- To integrate understanding and expression

- To discover polarizations that exist outside present awareness

- To stimulate awareness and the integration of conflicting forces

- To reveal competing commitments and integrate big assumptions

- To stimulate circumstances under which the individual, group, or organization can feel and act stronger, more competent, more self-supported, more explorative, and become actively responsible for self and responsible to others

Summary of Basic Change Activities

To grasp the depth of the Gestalt approach to OD, it is critical to remember that the process of creating perceptual awareness, and its resulting meaning-making, is a core component. As a means of attending to this core component, the Gestalt consultant will generally adhere to the following five practices:

1. Attending to the client system, observing and selectively sharing observations of what we see, hear, and so forth, thereby establishing our presence in the client system and increasing awareness.

2. Attending to our experiences (feelings, sensations, thoughts) and selectively sharing these, thereby establishing our presence as something most likely missing in the system.

3. Focusing on what gets done or is attended to (excitement) in the client system, and watching for the emergence of what does not get done or attended to, and acting to support the mobilization of energy so something happens.

4. Facilitating clear, meaningful, heightened awareness between members of the client system, and between ourselves and the client system.

5. Helping the client system achieve a heightened awareness of their process, so as to achieve closure within areas of unfinished business.

In practicing the Gestalt consulting stance, diversity and inclusion are becoming core components. The commingling of cultures through globalization suggests that Gestalt consultants, if practicing self-awareness, will be in a strong position to support individual and organization awareness with regard to the business justification -- as well as the humane imperative -- for inclusion. The diversity of the world is better understood in many other countries than it commonly is in the U.S. However, global leaders are beginning to receive training about cultural differences that stem from differing nationalities, ethnicities, and religions. It is in embracing these new perceptions that globalization can create inclusive organizations -- in fact, and not just “in word.” Gestalt consultants who have completed their personal work regarding issues of inclusion will therefore find themselves in a unique position to support global leaders and organizations in becoming truly inclusive.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Herb Stevenson is President/CEO of the global Cleveland Consulting Group, Inc. He has been a senior executive for over 25 years, and an executive consultant/senior executive coach for over 30 years. Earlier in his career, Stevenson was a turnaround specialist for failing banks, and has published 26 books on banking, and is listed in eight “Who’s Who” categories. A member of the faculty of the Gestalt Institute of Cleveland, he is a graduate of Cleveland State University’s Diversity Management Master’s degree program. Stevenson is additionally the founder of Natural Passages, a men’s awareness-enhancement program. He can be reached at: herb@clevelandconsultinggroup.com

REFERENCES

Parts of this article were adapted from Herb Stevenson, Emergence: The Gestalt Approach to Change (pp. 561-567) in Practicing Organization Development, edited by William Rothwell, Jacqueline Stavros, Roland Sullivan and Arielle Sullivan, 2009, 3rd Edition, Pfeiffer.

Agyris, C. (1986), Skilled Incompetence. Harvard Business Review, September-October, pp. 1-7.

Cross, Elsie Y. (2000), Managing Diversity -- The Courage to Lead. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger Publishers.

Dixon, N. M. & Ross, R. (1999), The organizational learning cycle. In: The Dance of Change, ed. P. Senge, A. Kleiner, C. Roberts, R. Ross, G. Roth, & B. Smith. New York: Doubleday/Currency, pp. 435-444.

Duncan, B. L. & S. D. Miller (2000), The client's theory of change: Consulting the client in the integrative process. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 10: 169-

187.

Fortune 500 (2016), http://fortune.com/fortune500/

Kaplan, M. & Donovan, M. (2013), The Inclusion Dividend: Why Investing in Diversity & Inclusion Pays Off. Boston: Bibliomotion.

Katz, J., Miller, F.A., Seashore, E.W., Cross, E.Y., ed. (1994), The Promise of Diversity: Over 40 Voices Discuss Strategies for Eliminating Discrimination in Organizations. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Klein, Donald C. (Ed.), The Humiliation Dynamic: Viewing the Task of Prevention From a New Perspective, Special Issue, Journal of Primary Prevention, Part I, 12, No. 2, 1991. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/ Plenum Publishers

Nevis, E. (1987), Organizational Consulting: A Gestalt Approach. New York: Gardner Press.

Perls, F., Hefferline, R., & Goodman, P. (1994), Gestalt Therapy: Excitement and Growth in Human Personality. Highland, NY: Gestalt Journal Press.

Perls, L. (1992), Concepts and misconceptions of Gestalt therapy. Journal of Humanistic

Psychology, 32 (3): 50-56.

Pillsbury, W. B. (1933) The units of experience—meaning or Gestalt. The Psychological

Review, 40 ( 6): 481-497

Polster, E., & Polster, M. (1973), Gestalt Therapy Integrated: Contours of Theory and Practice. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Ready, D. A. & Pebles, M.E. (Fall, 2015), Developing the next generation of

enterprise leaders. MIT Sloan Management Review. 57(1): 43-51.

http://mitsmr.com/10cPy2G

Senge, P. (1999), Establishing a pilot group. In: The Dance of Change, ed. P. Senge, A. Kleiner, C. Roberts, R. Ross, G. Roth, & B. Smith. New York: Doubleday/Currency, pp. 39-41.

Stevenson, H. (2005), Gestalt coaching. The OD Practitioner, 37 (4): 43-51.

Stevenson, H. (2010), Paradox: The Gestalt theory of change. Gestalt Review. 14 (1): 111-126

Stevenson, H. (2016). Coaching at the point of contact. Gestalt Review. In Process

Tapia, A.T., & Lange, D. (2015) The Inclusive Leaders. Korn Ferry Institute

Thiederman, S. (2013), The Diversity and Inclusion Handbook. Bedford, TX: The Walk the

Talk® Company.

Tomke, S. (2001). Enlightened experimentation: The new imperative for innovation.

Harvard Business Review, February: 67-75.

Williamson, Jr., T. S. (2002), Managing the workforce of the future. Texaco Task Force Case

Study, Texaco National Academies Press. http://www.nap.edu/read/10377/chapter/18

Winnicott, D. W. (1965), The Maturational Process and the Facilitating Environment. New York: International Universities Press.

Zinker, J. (1978), Creative Process in Gestalt Therapy. New York: Vintage Books.

We Appreciate Your Feedback

Please let us know if you found this article interesting or useful. We will not submit this information to any third parties.